New Emerging Technologies

New Emerging Technologies

Introduction

Neurotechnology is a broad term, encompassing any tool-based method of interacting with the brain. Driven by rapid technical development and neuroscientific research, it has exploded as a field in recent decades, inviting collaboration between biology, physics, computer science, materials science, and many engineering disciplines.

At its core, neurotechnology is working toward two types of interactions: “reading” information from the brain and “writing” information to the brain. (1) “Reading” can be done by noninvasive imaging methods such as MRI, or invasive methods like directly recording signals from neurons with implanted electrodes. “Writing” refers to activating neurons in specific ways, and can be done with a number of modalities, like electricity, sound, and light. Many exciting developing efforts aim to build “Read/Write” devices that “close the loop” between these two activities, allowing for more complex and capable self-regulating systems.

This module is meant to introduce some of the latest developments and improvements on these methods from a technical side, as well as addressing how they are being applied outside of the research lab.

Reading

Observing the brain is one of the oldest methods used to understand its function. By looking at neural patterns of activity and correlating them with organism behavior or capabilities, we have already been able to make great progress in our understanding.

While there are many tools already used to observe the brain (2), new innovations in this area are focused on overcoming the current limitations of those devices, while also building out downstream applications for the data. (Some basic considerations include invasive vs. non-invasive usage and higher temporal vs. spatial imaging resolution.)

One challenge is getting high quality data from specific brain areas in a non-invasive and more accessible way. To solve this, groups like Openwater, led by Mary Lou Jepsen, are building “wearable MRI” devices. Using new developments in optics and flexible electronics, this class of imaging sets out to address the cost and portability issues of MRI while providing spatial information currently unattainable from EEG devices. (3) These units could potentially be integrated into clothing for continuous monitoring and also target other internal organs besides the nervous system.

Even when invasive methods are used to get direct neural recordings, the data quality problems aren’t completely solved, as there are hardware difficulties to contend with! The stiff nature of metal recording electrodes triggers an inflammatory response and scar tissue production, which causes signal quality to degrade over time and shortening the time between surgeries to replace electrodes. It is also difficult to get signal out of the brain through the skull without leaving a permanently open surgical site. To address these, many groups are building new electrodes to be flexible and highly biocompatible to integrate with brain tissue, smaller to minimize scarring, and wireless to transmit data to external devices. (4, 5, 6)

“Neural dust” is a project from the Carmena lab at UCSC building a network of low-power, distributed recording devices that could be chronically implanted into the brain and work together to wirelessly transmit neural data from a relatively broad area. (7) The small footprint of each device would allow it to move with its surrounding tissue instead of remaining stationary, and each unit would be powered by and communicated with via ultrasound, allowing them to operate without external power cables.

Another method to create chronic implants takes the route of highly flexible electronics, using injectable electrode arrays that unfold into a mesh on the surface of the brain. (8, 9) This approach would allow neural implants with only very minimally invasive surgery. These arrays too would be able to move with the brain while reducing tissue damage and inflammation.

Writing

“Writing” to the brain, i.e. stimulating neurons in purposeful ways, opens up new possibilities for interaction. It can be used to help understand brain function by looking for changes resulting from the stimulation, but it is also increasingly used therapeutically to treat chronic pain, movement disorders, and some psychiatric disorders.

Innovations in this arena have been focused mainly on specificity of simulation and discovery of new stimulation modalities.

Unlike observational neural recordings, neural stimulation has classically been limited to invasive methods only, generally by applying direct electrical stimulation to a neuron. New modalities have recently been investigated, with an incentive to reduce the number of risky brain surgeries required to implant current stimulator devices. One such option is to deliver electrical stimulation to deep brain areas noninvasively, recently demonstrated by the Boyden lab at MIT. By stimulating with two high-frequency electrical currents, they were able to produce a targeted “beat frequency” at the points where the currents interfered with each other. (10) This method was able to successfully reach areas deep in the brain, previously only accessible by highly invasive deep brain stimulation (DBS) probes.

Read/Write

Taking any of “Reading” and “Writing” methods alone represents an “open-loop” system. This means that in each case, the information is only flowing one way, so there is no feedback available to improve the system or change its behavior.

This can be a problem for neural stimulation in particular if there is no immediate data about how the stimulator is affecting its targets. So far, in cases like spinal implants for chronic pain, this has been addressed by relatively frequent doctor visits and parameter tuning of the device, but this latency between turning the stimulation on and having someone evaluate the results could be months.

With more mature methods of recording and stimulation, there have been many successful projects to close the data loop and combine both technologies into more intelligent and adaptable systems. (11)

A first application is an improved version of the chronic spinal cord stimulator mentioned above. Rather than running without feedback, if a device knows the stimulation patterns it is using and takes those into account while recording, it can isolate what effects the stimulation is having on the surrounding neurons. These systems can adapt on the fly by adjusting the dosage of stimulation to have the best therapeutic effects. (12, 13)

Similarly, other systems listen to cortical activity for signs of epileptic seizure activity. When early signs of a seizure are detected, the device can immediately intervene by delivering stimulation meant to halt the spread of abnormal neural firing and stop the seizure. (14, 15) Systems like this, designed for immediate intervention, may be built for motor disorders or other patterns of neural activity as well.

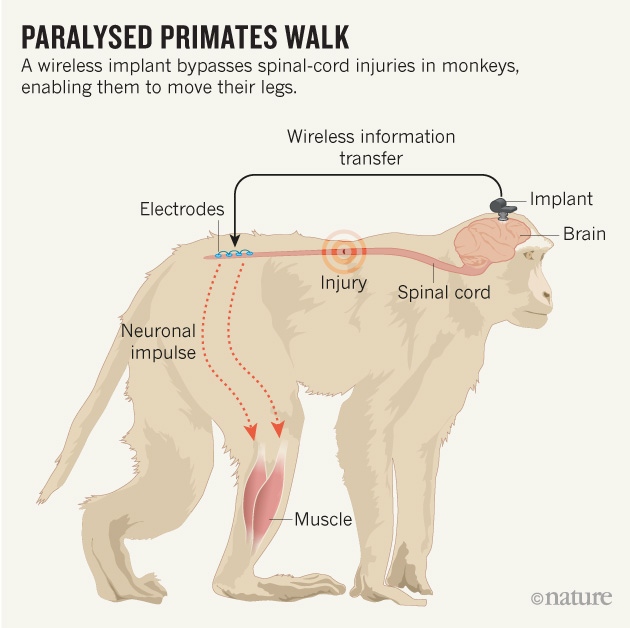

Separating the targets of recording and stimulation to different areas of the nervous system can also have compelling and restorative applications. Several groups have combined recording from motor areas in the brain with neural stimulation in lower limbs to regain the ability to walk in animals with spinal cord injury. (16, 17) By listening for characteristic patterns of activity signaling leg movements and using those as triggers for the lower-limb stimulation, the spinal cord damage was bypassed and the animals were able to walk using their own voluntary mental activity. This type of device has a promising future in overcoming paralysis and spinal cord damage. (18)

Applications and Public Perception

This section focuses on the changes within consumer brainwave (EEG) technologies in use cases and public perception, as well as outlooks and challenges to adoption as this technology continues to develop.

Healthcare Applications

Healthcare is, according to this 2018 market research report, the fastest growing opportunity for commercial EEG headbands and products. A global increase in chronic conditions and diseases along with associated demands on treatment facilities are creating a heavy cost burden for the current healthcare system. A recent PWC report suggests that the prevalence of these conditions and diseases is expected to increase rapidly in the coming years. That same report also states that emerging technologies will help alleviate these demands by providing a more patient-centric approach to health care solutions. There is the strong potential for commercial EEG products to fill this need by providing continuous in-home monitoring for patients with these conditions.

In 2015, a Las Vegas hospital held a 6-month long study on how brainwave headbands could help patients with pain relief. The researchers stated that this technology could “open the door to the future of connected care” and help build a more personalized patient-centric approach to health treatments. The study projected that the technology would help to lower costs while improving access to care. Other institutions such as the Canadian Medical Association, and the Ontario Brain Institute with its ONtrepreneurs program, are also exploring ways to include commercial EEG headbands into research and practice.

The global increase in chronic conditions and diseases, the dangerous impact those have on mental illness and overall health, and an overloaded health care system are increasing the need for affordable health management tools. The possible applications of EEG and commercial alternatives, which are already being demonstrated in healthcare research, will also be applied to areas such as mental health and education program innovations. As we take a more holistic approach to health with learning, diet, physical exercise, and meditation, commercial EEG will fulfill the unmet need for connected, affordable and personalized care options.

Wellness Applications

While the product options for EEG headbands are still limited, companies are exploring new form-factors and uses for their technology. Wellness focused applications, especially for meditation and productivity, are becoming a common product focus. Here are just a few examples:

Melomind - Melomind describes itself as a “relaxation companion”, a product designed to increase productivity, efficiency, and focus in all aspects of your life.

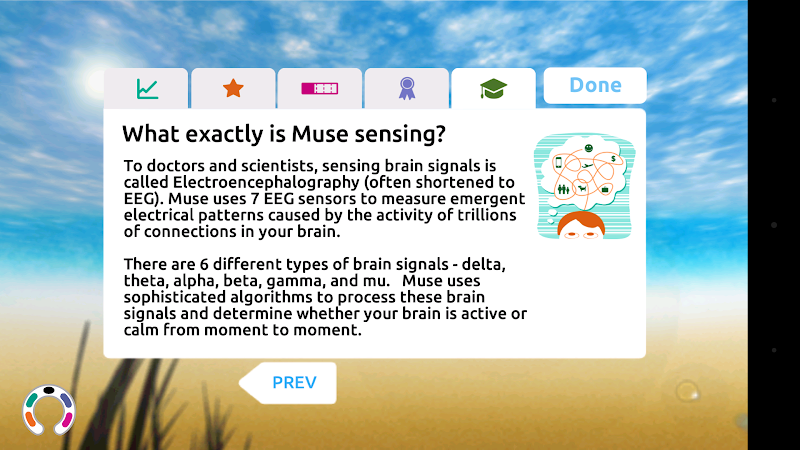

Muse - Muse is sold as a “personal meditation assistant”, with the product primarily used for mindfulness training. Their new product, the Smith Lowdown Focus sunglasses, is meant to enhance focus and concentration for sport performance.

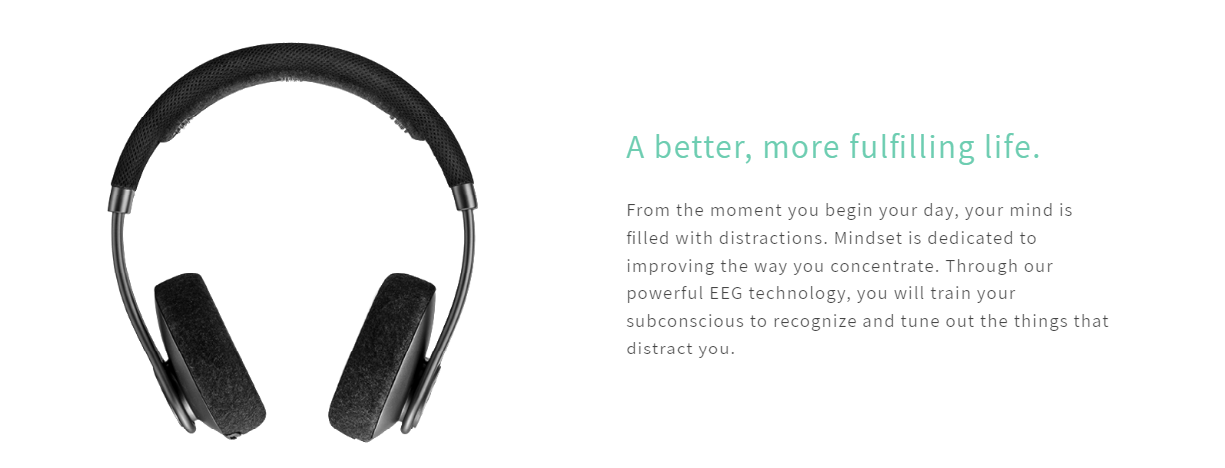

Mindset - Mindset is a pair of headphones designed with built-in EEG sensors. The headphones detect when you are losing focus, and provides auditory feedback to help bring you back on track.

Focusband - Focusband bills itself as the world’s first in-motion brain sensing headset, a brain training system that enhances focus and performance.

This list has more details on the types of headbands available

Wellness-focused applications have the ability to give tangible confirmations through visuals, dashboards, and numbers, on the impact of our lifestyle behaviour. If showing real-time cognitive performance can encourage healthy habits, the applications could also be used - one day - to help a person avoid the habits which trigger chronic conditions and diseases.

Product Terminology

One challenge for larger adaptation of commercial EEG products is how we talk about the technology. Companies creating commercial EEG products have a difficult task of finding balance between factual and emotional appeals, and determining what the right balance is for their platforms. You can see by the visuals below that the ways companies describe their products, and what the benefits are, have changed drastically over the past 4-5 years.

The Muse ‘Calm’ app in 2014

You can also read up on the evolution of the package design for Muse, created by Tera Rego.

Descriptions of the outcome of product use, not the science behind the product, are more common now. Words like focus, calm, insight, balance, productivity, relaxation, and ways to quiet the mind.

Emotiv in 2017

These all play to wider audience not familiar with the technology. These are examples of outcomes we might also strive for in our everyday and want to have. Integrating these desires into objects we’re familiar with could help increase awareness of the technology and benefits.

Melomind in 2017

For example, a headband is known as a comfortable clothing piece, worn for both fashion and exercise. Product labels such as ‘brain-sensing headband’ become relatable and refer to objects that already have a place in our lives, even while EEG and neurotechnology might not yet. They can become products that fulfill a desire like ‘being focused’ and living a healthier life, while also being scientifically validated. Our choices in objects, things such as a pair of sunglasses or headphones can represent part of a personal story in a tangible way. The technology may be able to achieve broader appeal when commercial EEG products can show how they fit into that story, and become ubiquitous.

Mindset in 2018

Brainsensing headphones (like Mindset) or sunglasses (such as Smith Lowdown Focus) help integrate a technology with familiar items we already wear and attach meaning and emotion to.

Outlooks

There are many opinions about what the future of commercial EEG headbands can look like, and this section provides only one.

If you are interested in reading some insights about the commercial EEG landscape, here is a great post by our very own NeuroTechX founder Yannick Roy.

Or this article, written by Loren Grush for The Verge in 2016. It’s an honest but scathing review on the the capabilities of currently-available commercial EEG devices.

One thing that sticks out, from the endless opinions you can find, is the potential future use of these products for health care. As Grush wrote in the above article:

“A likelier future than EEG-controlled cars are headbands that may aid people with disabilities. But for now, those technologies are still too young”

This ongoing research into the benefits of commercial EEG may give companies more ways to make science-backed claims about their products. The changes in terminology and increase in available product options may aide mainstream adoption and proliferation of the technology. Likewise, these changes will make it much easier for consumers to understand what the products actually do and why they should use them.

The diversification of EEG into wellness applications, along with the changes in language, could help humanize the technology and give the public more ways to relate to it. And with an already demonstrated global need for affordable and connected wellness tools, commercial EEG devices can give people a low-cost way of managing and making their health decisions autonomously. With the increase in awareness of the long-term benefits of a healthy lifestyle, an affordable and fashionable EEG device or headband which supports that, could become the linchpin of new and emerging commercial neurotech options.

References

- Disclaimer: this terminology isn’t technically correct! It is only meant here to intuitively indicate the direction of data flow. More accurate terms would be “recording” and “modulating”. “Reading” and “writing” have been used to set up an analogy of the brain to a hard drive, which is an outdated comparison. That analogy would imply a number of incorrect things about brain function, including an overestimation of how precisely we can decode neural information or elicit specific effects. For those reasons, I am not promoting that analogy.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroimaging

- https://www.openwater.cc/technology

- Lu, Y., Lyu, H., Richardson, A. G., Lucas, T. H., & Kuzum, D. (2016). Flexible Neural Electrode Array Based-on Porous Graphene for Cortical Microstimulation and Sensing. Scientific Reports, 6(1). https://www.nature.com/articles/srep33526

- Neely, R. M., Piech, D. K., Santacruz, S. R., Maharbiz, M. M., & Carmena, J. M. (2018). Recent advances in neural dust: towards a neural interface platform. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 50, 64–71. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29331738

- Schwarz, D. A., Lebedev, M. A., Hanson, T. L., Dimitrov, D. F., Lehew, G., Meloy, J., … Nicolelis, M. A. L. (2014). Chronic, wireless recordings of large-scale brain activity in freely moving rhesus monkeys. Nature Methods, 11(6), 670–676. https://www.nature.com/articles/nmeth.2936

- http://news.berkeley.edu/2016/08/03/sprinkling-of-neural-dust-opens-door-to-electroceuticals/

- Hong, G., Yang, X., Zhou, T., & Lieber, C. M. (2018). Mesh electronics: a new paradigm for tissue-like brain probes. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 50, 33–41. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959438817301952

- Zhou, T., Hong, G., Fu, T.-M., Yang, X., Schuhmann, T. G., Viveros, R. D., & Lieber, C. M. (2017). Syringe-injectable mesh electronics integrate seamlessly with minimal chronic immune response in the brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(23), 5894–5899. http://www.pnas.org/content/114/23/5894

- http://news.mit.edu/2017/noninvasive-method-deep-brain-stimulation-0601

- Cha, K.S., Yeo, D. & Kim, K.H. Biomed. Eng. Lett. (2016) 6: 113. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13534-016-0231-5

- https://neuronewsinternational.com/closed-loop-spinal-cord-stimulation-may-represent-new-paradigm-mitigate-tolerance/

- Russo, M., Cousins, M. J., Brooker, C., Taylor, N., Boesel, T., Sullivan, R., … Parker, J. (2017). Effective Relief of Pain and Associated Symptoms With Closed-Loop Spinal Cord Stimulation System: Preliminary Results of the Avalon Study. Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface, 21(1), 38–47. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28922517

- Pais-Vieira, M., Yadav, A. P., Moreira, D., Guggenmos, D., Santos, A., Lebedev, M., & Nicolelis, M. A. L. (2016). A Closed Loop Brain-machine Interface for Epilepsy Control Using Dorsal Column Electrical Stimulation. Scientific Reports, 6(1). https://www.nature.com/articles/srep32814

- https://www.epilepsy.com/learn/treating-seizures-and-epilepsy/devices/vagus-nerve-stimulation-vns

- Wenger, N., Moraud, E. M., Raspopovic, S., Bonizzato, M., DiGiovanna, J., Musienko, P., … Courtine, G. (2014). Closed-loop neuromodulation of spinal sensorimotor circuits controls refined locomotion after complete spinal cord injury. Science Translational Medicine, 6(255), 255ra133-255ra133. http://stm.sciencemag.org/content/6/255/255ra133

- Borton, D., Bonizzato, M., Beauparlant, J., DiGiovanna, J., Moraud, E. M., Wenger, N., … Courtine, G. (2014). Corticospinal neuroprostheses to restore locomotion after spinal cord injury. Neuroscience Research, 78, 21–29. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168010213002228

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/06/140625130137.htm