Introduction to Neuroscience

Table of Contents

- What is Neuroscience?

- The Nervous System

- Cellular Components of the Nervous System

- Neurochemistry

- Neuroanatomy and Brain Organization

- Functional Systems of the Brain

- Frontiers in Neuroscience

- References

What is Neuroscience?

Neuroscience is a study devoted to understanding the nervous system and its core component, the brain. This investigation can occur at multiple levels, from molecular synapses and cellular networks to cognition and behavior. Because of this, methods of inquiry and research are drawn from a number of disciplines, including molecular and cellular biology, physiology, biomedicine, behavioral science, cognitive psychology, electrical engineering, computer science and artificial intelligence.

Neuroscientists hope to understand how cellular circuits enable us to read and speak, how we bond with other humans, how we learn and retain information, how we experience pain, and how we feel motivation. They also hope to find causes for devastating disorders of the brain and body, as well as ways to prevent or cure them. Enormous progress has been made but we still don’t understand the full extent of how the brain works.

The Nervous System

The human nervous system is an extensive network of specialized cells that allow us to perceive, understand and act on the world around us. Neurons are the main functional unit of this network. They can generate electrical signals to quickly transmit information over long distances and pass them on to many other neurons. Glial cells support this network by cleaning, regulating, protecting, healing and insulating the neurons and their connections.

At the core of the nervous system, with over 100 trillion connections, is the human brain. Messages are relayed to the brain via the spinal cord, which runs down through the back and contains threadlike nerves that branch out to every organ and body part.

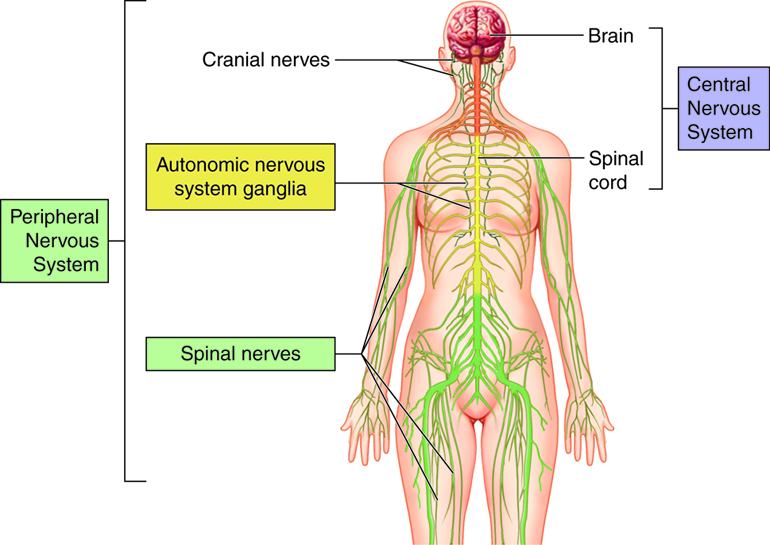

The nervous system is separated in two classes: the central and peripheral nervous systems.

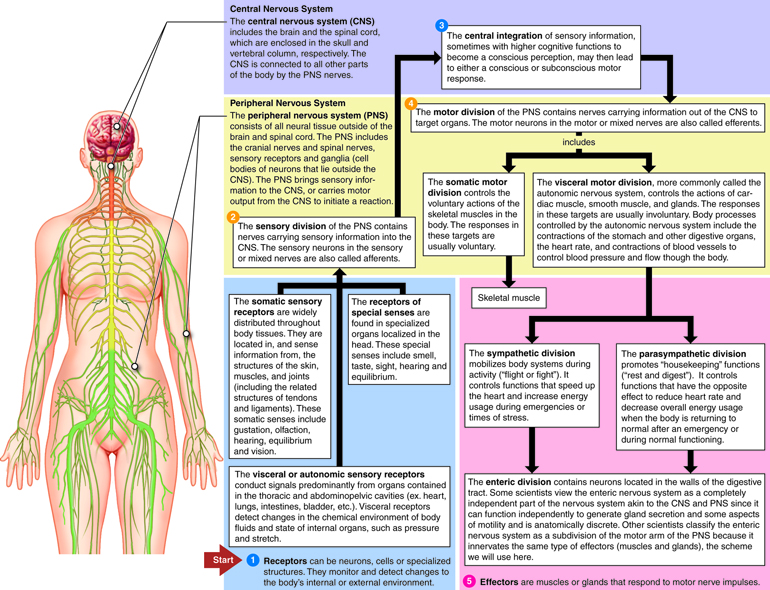

Divisions of the Nervous System

This work by Cenveo is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 United States

Central Nervous System (CNS)

The CNS consists of the brain and the spinal cord. It’s made of soft delicate tissue but it’s well protected by the skull and spinal vertebrae. The blood-brain barrier also prevents many toxins from entering the brain. The CNS acts as the control centre, sending and receiving information to and from muscles, glands, organs and others systems in the body through the Peripheral Nervous System. —

Peripheral Nervous System (PNS)

The PNS acts as a relay, transmitting information between the CNS and the rest of the body. Unlike the CNS, the PNS is not protected by the vertebral column and skull, or by the blood–brain barrier, which leaves it exposed to toxins and mechanical injuries.

The PNS includes a sensory division and a motor division.

Sensory Division

Also known as the afferent (conducting inwards) division, the sensory division receives sensory information from the body and sends it inwards to the CNS.

Motor Division

Also knows as the efferent (conducting outwards) division, the motor division receives information from the CNS and sends it out to the body.

The sensory and motor divisions each include a part of the somatic system and the autonomic system.

Somatic Nervous System

Sōma means ‘body’ in Greek so somatic means relating to the body. The somatic system relays information about most of the body’s conscious activity to and from the CNS. The somatic sensory receptors receive information from the senses and send it to the CNS while the somatic motor division sends information from the CNS to control the actions of the skeletal muscles.

Autonomic Nervous System

The autonomic nervous system primarily regulates involuntary or unconscious activity such as heart rate, breathing, pupil dilation, regulating glands and internal organs, blood pressure, digestion, and many other chemical processes that keep our body working. The autonomic sensory receptors receive information from these systems and send it to the CNS while the autonomic motor division sends information from the CNS to these systems. Although the word autonomic (from autonomy) means involuntary or unconscious, some of these activities are perceived and can be controlled consciously.

The autonomic motor division is divided into two complimentary subsystems: the sympathetic system and the parasympathetic system. Each is constantly working to shift the body to more prepared states and more relaxed states. The constant shifting of control between these two systems keeps the body ready for any situation.

Sympathetic Nervous System

The Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) prepares the body to react and expend energy in times of stress. When a potentially threatening experience occurs, the body reacts with what has been called the “fight-or-flight” phenomenon. The sympathetic system quickens the heart rate and breathing to increase oxygen, dilates pupils for better vision, reduces digestion to conserve energy, and prepares the muscles of the body to either defend or escape. This system is not only active for life-threatening situations; a project deadline or an urgent email might be stressful enough to trigger it.

Parasympathetic Nervous System

The Parasympathetic Nervous System (PSNS) helps the body “rest-and-digest”, conserving energy and maintaining functions under ordinary conditions. It slows the heart rate, stimulates digestion and other metabolic processes. This system is slow acting, unlike its counterpart, and may take several minutes or even longer to get the body back to a relaxed state after a stressful situation.

Receptors and Effectors

At the farthest branches of this network there are two basic types of neurons: receptors and effectors. Receptors are part of the sensory division as they receive information about changes in the environment. Effectors are part of the motor division as they produce changes in the body which can in turn effect the outside world.

Below is a diagram showing how signals move through the nervous system

Subdivisions of the Nervous System

This work by Cenveo is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 United States

If you would like to learn more about the nervous system there is an excellent video series by Crash Course on the topic.

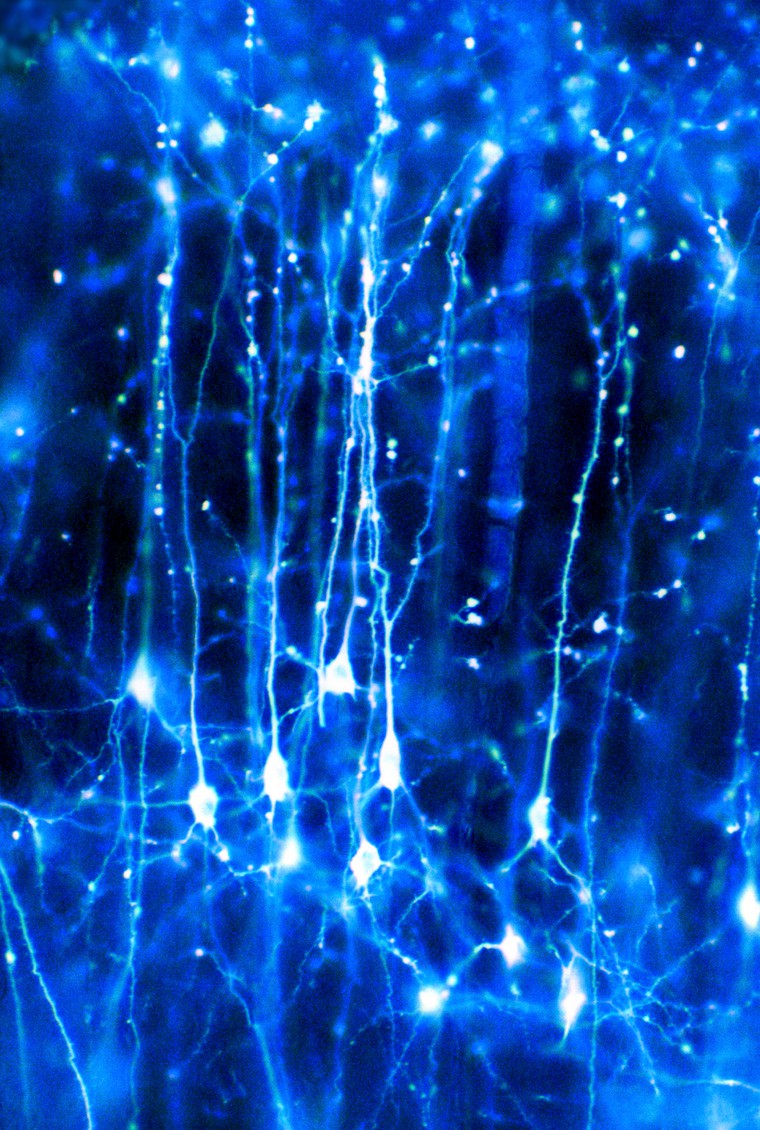

Cellular Components of the Nervous System

‘Neurons in the brain’ by Dr Jonathan Clarke. Credit: Dr Jonathan Clarke. CC BY

‘Neurons in the brain’ by Dr Jonathan Clarke. Credit: Dr Jonathan Clarke. CC BY

Neurons

Neurons are the cells that form a framework for communication throughout the nervous system. They can come in several shapes and sizes depending on their specialized functions but all neurons will have axons and dendrites that protrude from the cell body.

Dendrites

Most neurons have many short dendrites that receive signals, sending them inward towards the cell body as electrical impulses.

Axons

Most neurons have a single axon that typically sends electrical impulses outwards away from the cell body. Axons can vary in length from extremely short to over 1 m to reach from the base of your spine to your ankle.

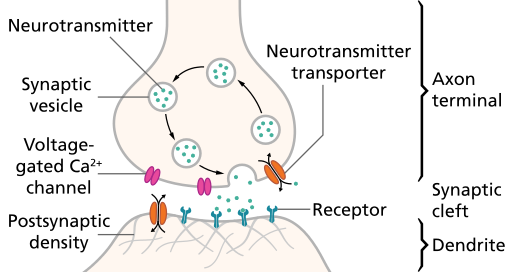

Synapse

Neurons communicate through axon-dendrite and sometimes dendrite-dendrite connections but these protrusions don’t actually touch. A small gap exists at this membrane-to-membrane junction point called a synapse. It contains molecular structures, or machines, that control energy by allowing electrical or chemical signals to be rapidly transmitted.

Neuron Communication

Neurons communicate electrochemically. An electrical signal from one neuron’s axon will trigger a release of neurotransmitters which bind to channels on another neuron’s dendrite. This causes the channels to open and receive positively-charged ions from the synapse. If this increases the charge enough, can trigger an action potential, causing that neuron to send an electrical signal (positive charge) down its own axon.

Neural Networks

A nervous system emerges from a large assemblage of connected neurons. A nerve impulse can also be transmitted from a sensory receptor cell to a neuron, from a neuron to a set of muscles or an endocrine gland. Any cell that receives a synaptic signal from a neuron may be excited, inhibited, or otherwise modulated.

Glial Cells

Glial cells mostly act as caretaker cells, supporting the neurons and their connections. There are several different types:

- Astrocytes

- Oligodendrocytes

- Ependymal cells

- Schwann cells

- Satellite cells

- Microglial cells

Neurochemistry

Neurotransmitters

Neurotransmitters are the biochemical messengers, or couriers, of information between cells, released from neurons at the presynaptic nerve terminal to cross through synapses where they may be accepted by a receptor site on the other side. A single neuron will produce several different neurotransmitters. A cascade of specific chemical reactions occurs after a synapse; these specific chemical reactions depend on the presence, absence, or combination of specific receptor types. These reactions affect the neuron with either excitation potential (depolarization) or inhibition potential (hyper-polarization). Excitation makes it more likely that an action potential will fire; inhibition makes it less likely that an action potential will fire. Neurotransmitters and their receptors influence behavior, learning, emotions, and sleep.

Following is a condensed list of neurotransmitters involved in the many functions of our bodies:

| Neurotransmitter | Role |

|---|---|

| Acetylcholine | Acetylcholine is a very widely distributed excitatory neurotransmitter that triggers voluntary muscle contraction and stimulates the excretion of certain hormones. It is involved in wakefulness, attentiveness, learning, memory, sleep, anger, aggression, sexuality, and thirst. |

| Dopamine | Dopamine correlates with movement, attention, and learning. Dopamine is involved in controlling movement and posture. It also modulates mood and plays a central role in positive reinforcement and dependency. |

| Norepinephrine | Norepinephrine is associated with alertness. neurotransmitter that is important for attentiveness, emotions, sleeping, dreaming, and learning. Norepinephrine is also associated with the “fight or flight” response. |

| Serotonin | Serotonin plays a role in mood, sleep, appetite, and impulsive and aggressive behavior. |

| GABA (Gamma-Amino Butyric Acid) | GABA is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS, contributing to motor control, anxiety regulation, vision, and many other cortical functions. |

| Endorphins | Involved in pain relief and feelings of pleasure and contentedness. |

Neuroreceptors

Neuroreceptors are structures on the surface or inside of cells that recognize and bind to specific neurotransmitters, hormones, or psychotropic drugs. The bind created by neuroreceptors acts with either excitatory or inhibitory action potential. Once bound, the receptor often changes shape, causing a chemical cascade of cellular action. These cellular actions can alter which genes are turned on or off and can make the cell more or less likely to release its own neurotransmitters. Each type of neurotransmitter might have multiple receptors, each with a different role to play. A distinct role of each neurotransmitter is determined by exactly which neurotransmitter is present and where it is connecting.

(note: neuroreceptors are also known as neurotransmitter receptors, neuron receptor sites, receptor sites, or receptors.)

Neuroanatomy and Brain Organization

Introduction to Neuroanatomy and Brain Organization

Recently it has become possible to understand, in much detail, the complex processes that occur within different areas and sections of our brain. This section introduces the anatomical makeup of our brain and its connected systems. In the following section we will learn how the brain is organized, and the functional purposes of different brain regions. We look at the surface anatomy of the human brain, its internal structure, and the overall organization of sensory and motor systems in the brainstem and spinal cord. Though a complete lesson of neuroanatomy is worthy of a thick textbook full of elaborate illustrations, common terminology used in neuroscientific research is highlighted below.

Introduction to Brain Individuality

It is important to note that no two human brains are exactly alike. Just as we recognize that individual fingerprints are specifically and uniquely formed, we must also recognize that brains are the same way; this adds to the continued complexity of studying the human brain. As an example in uniqueness, no two cortices of the brain are folded or pleated exactly the same way to the same measurements. With continued scientific research and better understanding, scientists who study the brain are moving away from a historical “one size fits all” brain model. Someday this new approach to brain research, along with other leading concepts such as precision research and neuroplasticity potential, may lead to a different understanding of the brain and future bespoke brain treatments.

What is the Brain?

One of the most fascinating and wondrous things in the universe exists within each of us: our brain. Considering everything our brain does, it is incredibly compact, weighing just 3 pounds packed with 100 billion neurons that give us the ability to sense, see, hear, smell, move, think, laugh, cry, speak, read, and remember. Our brain is uniquely structured with many sections and folds that provide it with enough surface area necessary to process and store all of the body’s important information.

Rotating Skull and Brain via Giphy

The Basics

Neuroscientists use common neuroanatomical terms to denote location, organization, and function. Here we introduce the basics. Perched on top of the spinal column, the brain is the epicenter of the human nervous system. It is the largest part of the central nervous system (CNS) and made up of three general areas: the brainstem, the cerebellum, and the cerebral cortex. The brainstem is involved with autonomic control of processes like breathing and heart rate as well as conduction of information to and from the peripheral nervous system, the nerves and ganglia found outside the brain and spinal cord. The cerebellum, adjacent to the brainstem, is responsible for balance and coordination of movement. Resting above these structures, the cerebral cortex quickly perceives, analyzes, and responds to information from the world around us. It handles sensory perception and processing as well as higher-level cognitive functions like perception, memory, and decision-making. These three areas work together seamlessly in healthy individuals, allowing the brain to coordinate necessary functions and behaviors from breathing to spatial navigation.

The cerebral cortex is divided into two hemispheres connected by the corpus callosum, a bridge of wide, flat neural fibers that act as communication relays between the two sides. While several popular books suggest this lateralization is important to function, most cognitive processes are represented by activation in both hemispheres. The exception is language - both Broca’s Area, an area important to language syntax, and Wernicke’s Area, a region critical to language content, reside on the left side of the brain. Otherwise, the two hemispheres are nearly symmetrical and each one is further subdivided into four major lobes: the occipital, the temporal, the parietal, and the frontal.

Brain Lobes

Four lobes are used to denote specific anatomical locations within the brain: Frontal Lobe, Occipital Lobe, Parietal Lobe, and Temporal Lobe. These lobes, or anatomical locations of the brain, are referred to when examining different brain functions.

There are 4 Lobes of the Brain

| Brain Lobe | Location and Role |

|---|---|

| Frontal | The large frontal lobe extends from behind the forehead back to the parietal lobe. It is the control center for executive functions including reasoning, decision-making, expressive language, higher level cognitive processes, orientation (person, place, time, and situation integration of sensory information), and the planning and execution of movement, or motor behavior. The Frontal Lobe can be referred to as the Motor Cortex. |

| Parietal | Above the temporal lobe and adjacent to the occipital lobe, the parietal lobe houses the somatosensory cortex and plays an important role in touch and spatial navigation, including the processing of touch, pressure, temperature, and pain. The Parietal Lobe can be referred to as the Somatosensory Cortex. |

| Occipital | The occipital lobe, located at the back of the brain, is the control center for the primary visual cortex, the brain region responsible for processing and interpreting visual information. The Occipital Lobe can be referred to as the Visual Cortex. |

| Temporal | Reaching from the temple back towards the occipital lobe, the temporal lobe is a major processing center for receptive language, memory and emotion. The Temporal Lobe can be referred to as the Auditory Cortex. |

Folds and Grooves

The cortex is an extended piece of neural tissue, gathered and pleated to fit inside the skull cavity. Each pleat has a bump and a fold groove, the gyrus and the sulcus.

As we have mentioned previously, no two brain cortexes are folded in the same exact way. Yet several of these folds are large and pronounced enough to merit specific names. They are used to specify location—but also may be referred to in discussions of function.

For example, the lateral sulcus is the inner fold that separates the temporal lobe from the frontal lobe. Adjacent to the lateral sulcus is the temporal gyrus. Both this groove and fold house the primary auditory cortex, where the brain processes sound information. Wernicke’s Area, the brain region critical to processing language, also resides on the temporal gyrus.

BCI Lab’s “Glass Brain” - a 3D Brain Visualisation via Neuroscape

3 Sections of the Brain: Forebrain, Midbrain, Hindbrain

The brain is made up of three main sections: the forebrain, the midbrain, and the hindbrain. Different studies may refer to specific activations in the superior frontal, middle frontal, and inferior frontal gyri in the frontal lobes.

In studies of motor function, mentions of primary motor cortex may also refer to a location between the precentral gyrus and the central sulcus at the top of the brain. Contrary to popular lay-press usage, the terms lobe and gyrus are not interchangeable. References to gyri and sulci can help give a more specific location on a particular lobe of the cortex.

For further reading, see lessons on The Human Brain, Regions of the Human Brain, Outline of the Human Brain, and Functional Specialization of the Brain.

Forebrain

The forebrain is the largest and most complex part of the brain. It consists of the cerebrum and a few other structures beneath it. The forebrain is the forward-most portion of the brain, controlling body temperature, reproductive functions, eating, sleeping, and any display of emotions.

The cerebrum is the folded and grooved area of the brain typically shown in illustrations of the brain. The cerebrum contains information that influences intelligence, personality, emotion, feelings, memory, speech, and movement. Four lobes of the cerebrum are assigned to the processing of these specific types of information: the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital.

The cerebrum also can be divided into two right and left hemisphere halves, which are connected in the middle by a band of nerve fibers called the corpus callosum. The corpus callosum enables the two hemispheres to communicate.

The outer layer of the cerebrum is called the cortex; this outer layer is also known as grey matter of the brain. Information collected by the five senses comes into the brain from the spinal cord to the cortex, to be directed to other parts of the nervous system for further processing.

Located in the inner part of the forebrain are the thalamus, hypothalamus, and the pituitary gland. The thalamus carries messages from the sensory organs like the eyes, ears, nose, and fingers to the cortex. The hypothalamus controls activities of the autonomic nervous system, regulating neurohormones and influencing pituitary hormones, and controlling body temperature, tiredness, sleep, circadian rhythms, hunger, thirst, and behaviors related to parenting attachment. The pituitary gland secretes hormones that control thyroid glands and metabolism, blood pressure, some functions of sex organs, as well as some aspects of pregnancy and growth, childbirth, nursing, water/salt concentration at the kidneys, temperature regulation and pain relief.

Midbrain

The midbrain is considered part of the brainstem, located underneath the middle of the forebrain, and acting as a master coordinator for messages between the brain and the spinal cord. The midbrain is our Dopamine production center. Primarily, the midbrain relays information related to vision, hearing, and motor control, as well as sleep/wake cycles, alertness, arousal, excitation, motivation, habituation and regulation of body temperature. The human midbrain shares general architecture with the most ancient of vertebrates.

Hindbrain

The hindbrain sits underneath the back end of the cerebrum, including the cerebellum, pons, and medulla. The cerebellum is sometimes called the “little brain” because it looks like a small version of the cerebrum; it is responsible for balance, movement, and coordination. The pons and the medulla, make up the brainstem, along with the midbrain. Together, the pons, medulla, and midbrain coordinate all of the brain’s messages, and control many of the body’s automatic functions such as heart beats, breathing, blinking, digestion, and blood pressure.

Brodmann Areas and Talairach Coordinates

(currently editing)

Grey and White Matter

The brain is made up of both grey and white matter. Grey matter consists of the cell bodies and dendrites of the neurons, as well as supporting cells called astroglia and oligodendrocytes. White matter, however, is made up of mostly of axons sheathed in myelin, an insulating-type material that helps cells propagate signals more quickly. It’s the myelin that gives the white matter its lighter color. For many years, neuroscientists believed white matter was simply a support resource for gray matter. However, recent studies show that white matter architecture is important in supporting cognitive processes like learning and memory.

Connections Between the Sections

When studying the brain, it is important to emphasizes the importance of collaborative connections and networks.

The size and structure of our neocortex, or frontal lobes, represents the most recent biological evolution of the human brain. The neocortex works to help us make sense of the world around us by closely collaborating with the subcortical brain areas near the brainstem. Subcortical brain structures share information in both a bottom-up and top-down fashion with the neocortex.

Typically the brain and spinal cord act together; however, there are some actions, such as those associated with pain reflexes, where the spinal cord acts before the information enters the brain for processing.

Modern neuroimaging research is no longer focused on functional segregation, or the localization of function to a single area of the brain. Today, researchers are using new techniques to follow tracts of neurons that connect networks of brain areas to better understand how they work together to determine human behavior.

Connecting Neurons via Giphy

Functional Systems of the Brain

Through our senses, our brains are provided with information about light, sound, temperature, body part orientation and position, pressure of the atmosphere around us, the chemicals in our bloodstream, and more. Our senses collect and transfer information to our brains where it is used to determine what actions we should take. Our brains process this raw data in order to extract information about our environmental situations. Next our brains combine the processed information with information about our current needs and past memories. On the basis of results, our brains generate motor response patterns. These signal-processing tasks require intricate interplay between a variety of functional systems.

The function of our centralized brain is to coherently control our actions; our brains allow groups of muscles to be collaboratively activated in complex patterns, and stimuli influencing one part of the body to evoke responses in other parts, while at the same time preventing different parts of the body from acting at cross-purposes to each other.

Sensory Systems and Perception

This section introduces the neural foundations of sensory perception, where our sense of self relates to stimuli in the world around us. Our senses are useful in our daily lives because of the processing that happens in our brains. Sensory stimuli enters our neurological systems as physical energy absorbed from the world around us; this energy is then converted into neural signals to be processed in the brain, eventually revealing sensory experiences in our lives.

At a very basic level, sensory systems are made up of receptors, neural pathways, and parts of the brain involved in sensory perception. Each sensory system begins with specialized receptor cells. Commonly recognized sensory systems include the following five: vision, hearing, taste, smell, and touch.

Sight and Vision

Every sight we experience is the result of light entering the eye and forming an upside-down image on the retina layer of our eye. Our retina contains photoreceptors, light detecting cells that transform the light into nerve signals for the brain. The cortex of the brain receives the nerve signals, flips the images right-side up, and tells us what we are seeing so as to make sense of each vision experience, allowing us to react to what we see.

Hearing

Every sound we hear is the result of sound waves entering our ears and causing our eardrums to vibrate. These vibrations transfer along the middle ear and are converted into nerve signals which are received and processed by the cortex. The cortex helps us make sense of each sound experience, allowing us to react to what we hear.

Taste and Smell

Every taste we experience is the result of small groups of sensory cells on our tongue, our taste buds, reacting to chemicals in foods and sending messages to the areas in the cortex responsible for receiving and processing taste. Every smell we experience is the result of olfactory cells in our nostrils reacting to chemicals we breathe in, sending messages to the areas in the cortex responsible for receiving and processing smell. Our cortex processes and narrates taste and smell experience for us, allowing us to react to what we taste and smell.

Pain and Touch

Every time we experience pain or touch, it is the result of more than 4 million sensory receptors on the skin absorbing information related to temperature, texture, pressure, and pain. Simply put, our sensory receptors send this information to our cortex for processing, allowing us to react to what we sense through our skin.

More in-depth information on the topic of senses and reaction can be found by reading advanced lessons on Sensory-Motor Coupling, etc.

Motor Systems

This section introduces the neural foundations of our motor systems, examining at a very basic level the organization and function of the brain as well as the spinal mechanisms that govern voluntary bodily movement. Motor systems are areas of the brain that are involved in initiating body movement. Except for the muscles that control the eye, which are driven by nuclei in the midbrain, all the voluntary muscles in the body are directly innervated by motor neurons in the spinal cord and hindbrain.

Body Movement and Motor Control

Movement and motor control is the process by which we use our brain to stimulate and coordinate the muscles and limbs involved in the performance of a motor skill. Our neurological Motor System is necessary for interaction with the world, supporting basic balance and stability as well as physical action and reaction through body movement. At a very basic level, we absorb sensory information to determine the appropriate muscle and joint activation to move or act. Body movement requires not only muscles, mechanics, and physical coordination, but also neurological information processing and cognition. The Central Nervous System and the Musculoskeletal System interact cooperatively to control and support body movement.

More in-depth information on the topic of motor systems involved in body movement can be found by reading advanced lessons on The Motor System, Motor Coordination, Motor Control, Motor Cortex, and Spinal Mechanisms of Motor Control.

Arousal and Sleep Cycles

As humans we alternate between sleeping and waking cycles, arousal and alertness. These cycles are modulated by a network of brain areas and a central biological clock, and can be distinguished by specific brain activity patterns. Activity patterns of our neurons inside this biological clock rise and fall rhythmically, usually on a 24 hour cycle.

Homeostasis

Our ability to regulate our internal environment of our body is known as homeostasis. Maintaining homeostasis is a crucial function of the brain; the part of the brain that plays the greatest role in homeostasis is the hypothalamus. The basic principle that underlies homeostasis is maintaining balance within our body systems in order to survive. Our survival requires maintaining a variety of parameters of bodily state within a limited range of variation: these include temperature, water content, salt concentration in the bloodstream, blood glucose levels, blood oxygen level, etc.

The hypothalamus receives input from sensors located in the lining of blood vessels, conveying information about temperature, sodium level, glucose level, blood oxygen level, and other parameters. These hypothalamic nuclei send output signals to motor areas that can generate actions to rectify deficiencies. Some of the outputs also go to the pituitary gland, which secretes hormones into the bloodstream, where they circulate throughout the body and induce changes in cellular activity.

Cognition Systems and Brain Development

Learning is a complex function of the brain. Almost all animals are capable of modifying their behavior as a result of experience. Because behavior is driven by brain activity, changes in behavior must somehow correspond to changes inside the brain.

Intelligence, Learning and Memory

While learning, messages travel repeatedly between our neurons, establishing connections and neural pathways in our brains. Our neuron are finite; all the neurons we will ever have are established at birth. Young brains are highly adaptable and resilient, containing the potential for a lifetime of neural pathways to be forged throughout development. As the brain ages it is more difficult to master new tasks or change established behavior patterns because the brain must work harder to forge new neural pathways. Many scientists believe in the importance of challenging our brains throughout life to learn new things in order to continue forging new neural pathways.

Memory is another complex function of the brain. Everything we learn, experience, or sense is first processed in the cortex. If this information is important enough to transfer into long-term memory storage, it is sent to other regions of the brain such as the amygdala or hippocampus for information retrieval at a later date. As our experiences travel through the brain as messages, neural pathways are created. These neural pathways serve as the foundation of our memory.

Neuroscientists currently distinguish several types of learning and memory that are implemented by the brain in specific and distinct ways: working memory, episodic memory, semantic memory, instrumental memory, and motor learning.

More in-depth information on the topic of cognitive systems, cognitive neuroscience, and brain development can be found by reading advanced lessons on Cognition, Cognitive Neuroscience, Cognitive Science, Cognitive Biology, Cognitive Development, Neural Development, Brain Development, The Brain Prize 2014, Cognitive Flexibility, and Artificial Intelligence.

Brain Disease and Disorders

In this section we mention the most common brain disorders and explain at physiological level what is happening to the brain.

Things That Can Go Wrong With the Brain

Sometimes things can go wrong inside the brain. Because the brain is the body’s control center, when something goes wrong with it, it’s often serious and can affect many different parts of the body. In the 21st century, neuroscientists hope not only to uncover the secrets behind our most devastating neurological diseases, but how the brain makes us who we are. Neuroscientists work to understand how the brain affects mental life and behavior, in both health and disease states. More than 1,000 disorders of the brain and nervous system result in more hospitalizations and lost productivity than any other disease group, including heart disease and cancer. Neurological diseases make up 11 percent of the world’s disease burden. Inherited diseases, brain disorders associated with mental illness, and head injuries all can affect the way the brain works as well as present challenges to the rest of the body for daily activities. Problems that can affect the brain include brain disease, developmental disorders, degenerative disorders, psychiatric disorders, and behavioral disorders. Following are a few examples:

Brain Tumors

A brain tumor is an abnormal tissue growth in the brain. A tumor in the brain may grow slowly and produce few symptoms until it becomes large, or it can grow and spread rapidly, causing severe and quickly worsening symptoms.

Concussion and Head Injuries

A concussion is the temporary loss of normal brain function as a result of an internal head injury. An internal head injury could have serious implications. Internal injuries may involve the skull, the blood vessels within the skull, or the brain. Repeated concussions can result in permanent brain injury.

Cerebral Palsy

Cerebral palsy is the result of a developmental defect or damage to the brain before or during a baby’s birth, or during the first few years of a child’s life, affecting the motor areas of the brain. A person with cerebral palsy may have average intelligence or can have severe developmental delays or intellectual disability. Cerebral palsy can affect body movement in many different ways, from minor muscle weakness of the arms and legs to more severe motor impairment affecting walking and talking.

Epilepsy

This condition includes a wide variety of seizure disorders. Seizures involve either specific or more generalized areas of the brain, exhibiting minor to major symptoms with the most extreme cases being uncontrolled movements of the entire body and loss of consciousness. The specific cause is unknown in many cases, although epilepsy can be related to brain injury, tumors, or infections. The tendency to develop epilepsy may be genetic.

Meningitis and Encephalitis

Meningitis is an inflammation of the coverings of the brain and spinal cord, and encephalitis is an inflammation of the brain tissue. Both cases of inflammation involve infections of the brain and spinal cord, caused by bacterial or viral infections. Both conditions may cause permanent injury to the brain.

Mental illness

Mental illnesses are psychological and behavioral in nature and involve a wide range of problems in thought and function. Certain mental illnesses are now known to be linked to structural abnormalities or chemical dysfunction of the brain. Some are inherited. But often the cause is unknown. Injuries to the brain and chronic drug or alcohol abuse also can trigger some mental illnesses. Signs of chronic mental illnesses such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia may first show up in childhood. Mental illnesses that can be seen in younger people include depression, eating disorders such as bulimia or anorexia nervosa, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and phobias.

Neurotransmitter Imbalances

Neurotransmitter imbalances can involve a wide range of problems in thought and function. Following are a few examples of neurotransmitter transmission involved in brain disease and disorder:

- Alzheimer’s Disease (Acetylcholine)

- Parkinson’s Disease tremors and muscular rigidity (Dopamine)

- Schizophrenia (Dopamine)

- Epilepsy (GABA)

- Anxiety Disorders (GABA, Serotonin)

- Huntington’s Disease and trembling (GABA)

- Alzheimer’s Disease and memory malfunctions (Glutamate)

- Manic Depression and mood disorders (Norepinephrine)

- Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (Serotonin)

- Depression (Dopamine, Serotonin)

Frontiers in Neuroscience

Neuroscience will transform the 21st century the way that quantum physics did for the 20th century. Even breaking the genetic code was just the beginning in the launch of higher understanding about the human body, and specifically the brain. Understanding the miraculous workings of the brain and the nervous system is the vast mission of the relatively young field of neuroscience. In recent years, research techniques and theoretical advances in neuroscience have expanded tremendously, aided by molecular and cellular studies of individual neurons, neural networks, and imaging of sensory and motor tasks in the brain.

Better knowledge about brain function is still needed to treat neurological and psychiatric disorders, lessening their impact on individuals, families, and society. With better neuroscience knowledge, we will better understand who we are: our thoughts, emotion, creativity and morality. We will design who we will be, modifying our abilities, knowledge and ways of being.

References

Lesson will review and expand upon topics covered within the following resources:

“Neuroanatomy”. Duke University, Coursera. “Medical Neuroscience”. Duke University, Coursera. “Intro to Neuroscience”. MIT OCW. 2007 “The Fundamentals of Neuroscience”. Harvard University, HarvardX Neuroscience and EdX. “Neuroscience Online”. Department of Neurobiology, McGovern Medical School at UTHealth. “Big Ideas in Neuroscience”. Stanford University Neurosciences Institute. “What is Neuroscience?”. McGill University Dept of Neuroscience. “Brain Facts”. BrainFacts.org “Neuroscience: The Science of the Brain”. British Neuroscience Association & European Dana Alliance for the Brain. Richard Morris (University of Edinburgh) and Marianne Fillenz (University of Oxford). 2003. “Scanning the Brain”. American Psychological Association. “About Neuroscience”. Society for Neuroscience. “Neuroscience”. The Kavli Foundation. “Fundamentals to Neuroscience”. Wikiversity. “History + Timeline, Brain and Cognitive Sciences”. MIT. 2002 “History of Neuroscience”. University of Washington. 2014. “A Timeline of Neuroscience”. Serendip Studio, Bryn Mawr College. 2000.