Cellular Components

Neurons

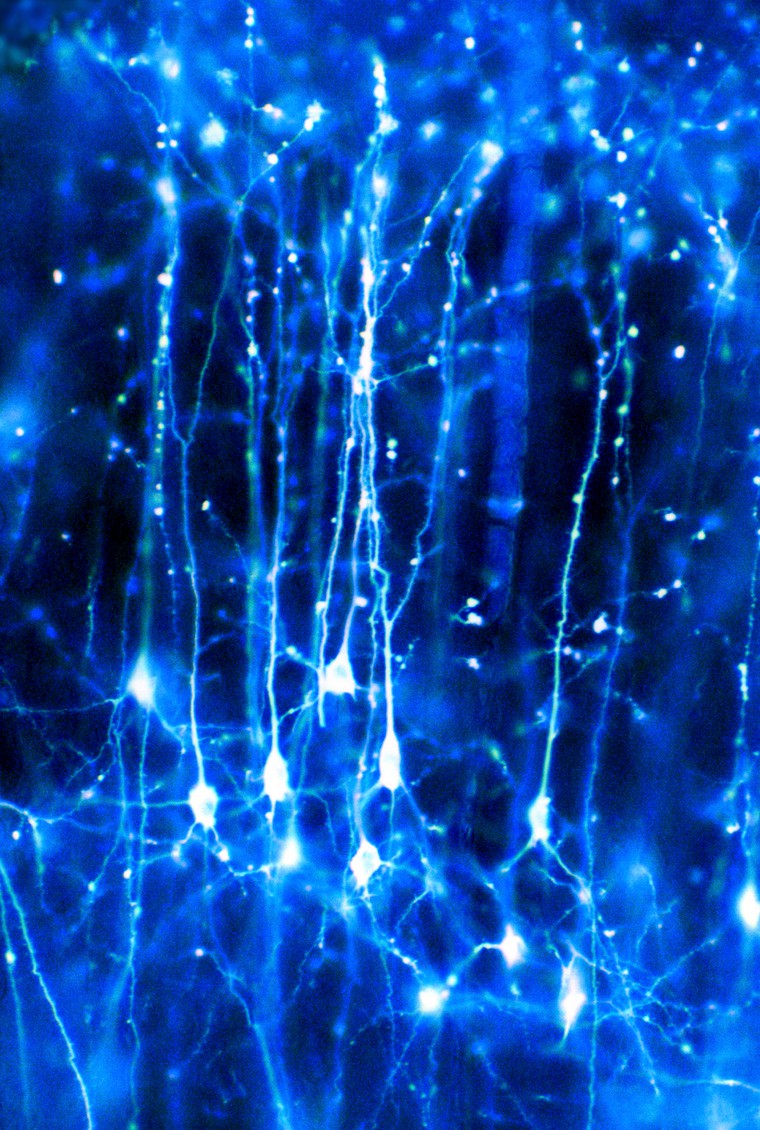

Neurons are the largest population of cells in the nervous system that specialize in communication. Estimates vary but there appear to be approximately 100 billion neurons in the brain. They can come in several shapes and sizes depending on their specialized functions but all neurons will have axons and dendrites that protrude from the cell body.

Neurons in the brain Credit: Dr Jonathan Clarke. CC BY

Dendrites

Dendrites are specialized structures for receiving and integrating signals from other cells. They do this mainly through receptors for small molecules and even for gases (Nitric Oxide). Dendrites often connect to the specialized structure at the end of an axon.

Axons

Most neurons have a single axon that typically sends electrical impulses outwards away from the cell body. Axons can vary in length from extremely short to over 1 m to reach from the base of your spine to your ankle. Axons can also have branches, or collaterals, that can connect with other cells, or groups of cells. The axons of the neurons in the peripheral nervous system are also known as nerves.

Synapse

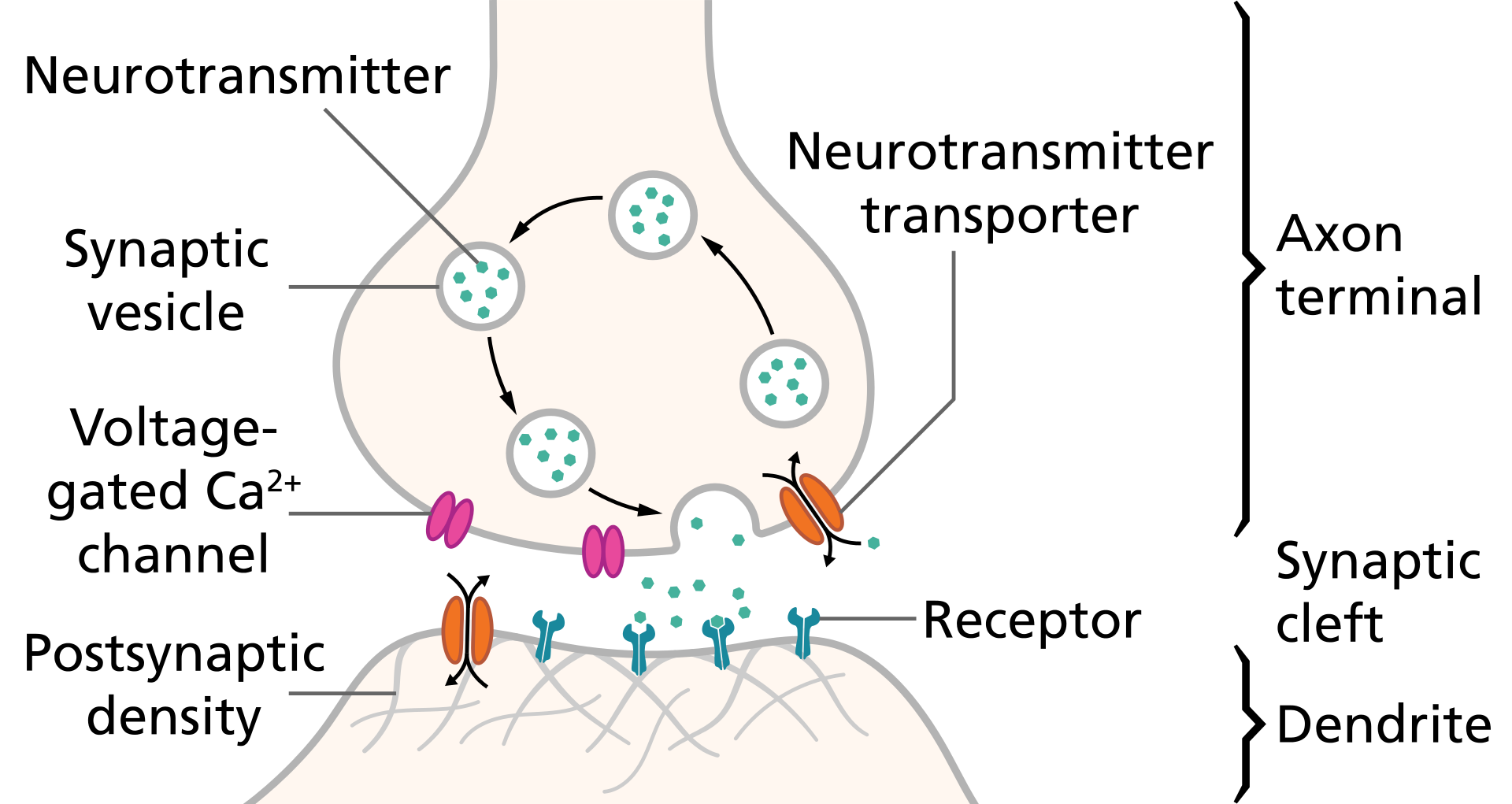

Neurons communicate through axon-dendrite, axon-soma and sometimes dendrite-dendrite connections but these protrusions don’t actually touch. A chemical synapse consists of a small gap between two neurons, with specialized proteins at both the presynaptic and postsynaptic membrane. Processes activated by these electrical signals at the presynaptic membrane of the end of one axon result in a downstream cascade leading to the release of chemicals called neurotransmitters. Other electrical synapses also exist between cells that are very close to each other and contain specialized tunnel-like structures, called gap junctions, allowing electrical signals to travel through them.

Synapse schematic Credit: Thomas Splettstoesser (www.scistyle.com). CC BY-SA 4.0

Neuronal Communication

An electrical signal from one neuron’s axon will trigger a release of neurotransmitters which bind to channels on another neuron’s dendrite. This causes the channels to open and receive positively-charged ions from the synapse. If this increases the charge enough, can trigger an action potential, causing that neuron to send an electrical signal (positive charge) down its own axon.

Chemical Synapse

Neural Networks

A nervous system emerges from a large assemblage of connected neurons. Nerve impulses can also be transmitted in a multitude of ways: from a sensory receptor cell to a neuron; from a neuron to a set of muscles or an endocrine gland; from an astrocyte to a neuron. Any cell that receives a synaptic signal from a neuron may be excited, inhibited, or otherwise modulated.

Glial Cells

Glial cells mostly act as caretaker cells, supporting the neurons and their connections. There are several different types:

Astrocytes1: These are often considered a third component of synapses as they are intimately connected with neurons. Their functions include recycling excess neurotransmitter, releasing its own transmitters to modulate the synapse and providing protection from cellular damage or injury.

Oligodendrocytes: These are myelinating cells in the central nervous system. They surround the axons of neurons with a fatty, myelin sheath that insulates the electrical signal and allows for quicker communication.

Ependymal cells: These are cells which line part of the brain called ventricles, which have finger-like projections called cilia. These regions in the brain are chambers that are filled with cerebrospinal fluid, produced by ependymal cells, and they bathe both the brain and the spinal cord. These calls may also be involved in the migration of new neurons being formed (at least in rodents)2. For a more extensive review, see footnotes3.

Schwann cells: These are the myelinating cells of the PNS which can also insulate the electrical signals travelling through axons. They also act to speed up the neural signalling. The effect of demyelination can be seen in related disorders such as multiple sclerosis

Microglial cells: These are the resident immune cells of the brain (up to 10% of brain cells). They are also involved in synaptic pruning/neurodevelopment and can also release molecules for other immune cells to recognize4. Microglia can become activated into a pro-inflammatory or an anti-inflammatory state, both of which change the shape of the cell as well as the types of molecules that it releases into the environment.

Neurochemistry

Neurotransmitters

Neurotransmitters are the biochemical messengers, or couriers, of information between cells, released from neurons at the presynaptic nerve terminal to cross through synapses where they may be accepted by a receptor site on the other side. A single neuron will produce several different neurotransmitters. The effect of a neurotransmitter is dependent on the receptor that it binds; depending on the receptor’s machinery, it may result in changes affecting the excitability of the cell or even more subtle chemical and molecular changes.

Following is a list of the prominent neurotransmitters involved in the many functions of our bodies:

| Neurotransmitter | Role |

| Glutamate | Major excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain involved in learning, memory, synaptic plasticity and development. It is also involved in cell death - because overstimulation of a neuron with glutamate can cause excitotoxicity. |

| GABA (Gamma-Amino Butyric Acid) | GABA is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS, contributing to motor control, anxiety regulation, vision, and many other cortical functions. |

| Acetylcholine | Acetylcholine is a very widely distributed excitatory neurotransmitter that triggers voluntary muscle contraction and stimulates the secretion of certain hormones. It is involved in wakefulness, attentiveness, learning, memory, sleep, anger, aggression, sexuality, and thirst. |

| Dopamine | Dopamine correlates with movement, attention, and learning. Dopamine is involved in controlling movement and posture. It also modulates mood and plays a central role in positive reinforcement and dependency. |

| Norepinephrine | Norepinephrine is associated with alertness. neurotransmitter that is important for attentiveness, emotions, sleeping, dreaming, and learning. Norepinephrine is also associated with the "fight or flight" response. |

| Serotonin | Serotonin plays a role in mood, sleep, appetite, and impulsive and aggressive behavior. |

| Endorphins | Involved in pain relief and feelings of pleasure and contentedness. |

Receptors

Receptors are protein structures on the surface or inside of cells that recognize and bind to specific neurotransmitters, hormones, or psychotropic drugs. Once bound, the receptor then changes shape to exert a specific effect - this may involve altering the charge of the cell by opening or closing ion channels, or more subtle effects by impacting which genes in the cell are activated. This impacts the function of the neuron; it is important to note that the effect of a neurotransmitter is entirely dependent on the receptor to which it is bound.

Footnotes

Eroglu, C. and Barres, B.A., 2010. Regulation of synaptic connectivity by glia. Nature, 468(7321), p.223. ↩

Sawamoto, K., Wichterle, H., Gonzalez-Perez, O., Cholfin, J.A., Yamada, M., Spassky, N., Murcia, N.S., Garcia-Verdugo, J.M., Marin, O., Rubenstein, J.L. and Tessier-Lavigne, M., 2006. New neurons follow the flow of cerebrospinal fluid in the adult brain. Science, 311(5761), pp.629-632. ↩

Del Bigio, M.R., 1995. The ependyma: a protective barrier between brain and cerebrospinal fluid. Glia, 14(1), pp.1-13. ↩

Bilbo, S.D. and Schwarz, J.M., 2012. The immune system and developmental programming of brain and behavior. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology, 33(3), pp.267-286. ↩